LANSING RIVERFRONT

QUESTIONS. We began with questions that were simple, physical, and topographic. How do we get down to the River? Can we redefine the City’s relationship with its River? Could water be here, between our toes, as well as headed toward our taps? Can we create joy and utility in the same place?

PROJECT. The project’s landscape, where the Grand River meets downtown Lansing, has been most valued in the city’s history by reserving it for industrial uses. The River has been held away by walls, taken in, distributed, harnessed for power, and measured when necessary to keep us dry.

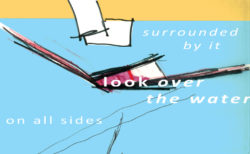

In a shift of collective thinking mirroring a global trend, Lansing has reevaluated its River-City interface, now reserving it for immediate and intimate public use. As part of that reassessment of values, the City has charged HAA’s team with the task of creating a new public riverfront along both sides of the Grand River between the Shiawassee Street Bridge and Ottawa Street. To the west, the project meets the Accident Fund’s new corporate headquarters. To the east, it interacts with the relocation of Lansing’s City Market. On both sides, it connects to Lansing’s River Trail.

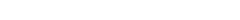

POSITION. The imperative of creating a new place, unquestionably public, guided every design decision. Every proposed intervention worked to choreograph new adjacencies: places of former production (the Board of Water and Light power station), places of commerce and our daily engagements (the new use of the station as the Accident Fund’s corporate headquarters with at least 500 new daily lunch breaks in downtown Lansing), and new public places like the adjoining City Market (to enjoy the fruits of our industry and commerce).

New physical relationships (the answers to our questions) are almost always told in sections—prepositional phrases in our grammar of place design. We could look over the water and be surrounded by it on all sides. We could step down to it, even into it. We could walk along it with our lunchmates. We could skim right over it by canoe, and we may now find a place to land. We could bring the River inside the place and modulate its edge with a condition that lies between water and land.

PROCESS. Beyond answering the topographic questions, we challenged ourselves to think about how to mark—as clearly owned and embraced by the public—this redefined landscape. The place was once collectively understood as off-limits. How could we mark it now?

In Lansing, we mark it by putting our foot down. One morning this May, hundreds of Lansing citizens also put their feet down onto 6” x 12” stamp pads to make footprint images. We used the images to design concrete stamps for marking the new riverfront landscape walk. As members of the public and as designers, we loved this. It was tactile, memorable, and fun. As the team responsible for the execution of a simple concept, it made us nervous.

We found ourselves navigating David Pye’s continuum between the workmanship of risk and the workmanship of certainty, described in The Nature and Art of Workmanship. We wanted to give the River back to the public. We wanted people to mark it and make it their own. Couldn’t we just have Miss Brown’s second graders walk through the construction site while the concrete is curing?, one of us asked. That is the extreme of risk. It would be fun, but we might not like the result. Pye uses the analogy of handwriting to explain this approach. The quality of the product could be spoiled at any moment.

Why don’t we just do it in the office?, another of us asked. We can do this in Photoshop. Some of us have kids; that’s how we’ll get the little feet. Do we need bike and wheelchair and dog prints too? We can find those on the internet. We’ll email the image to the fabricator, draw a detail in the documents, and write careful instructions for placing the mats. That is the extreme of certainty. It wouldn’t be very fun, but it would work. Pye uses the analogy of modern printing to explain this approach. We’d take out most of the risk to ourselves and “our work,” but we’d miss the link of meaning for the people we promised to take to the River.

Instead of either extreme, we settled on an intermediate form of workmanship that Pye explains with the analogy of typewriting. We took long rolls of paper out to the River. We purchased black stamp pads that were larger than we imagined existed. The Parks Department brought messier tubs of colored paint. The pads with black ink worked. The paint were more fun, even for our team member who still tried to tell every squealing, sliding kid exactly how to do it. Back in the office, we still relied on digital manipulation. We assured ourselves of most possible certainties, but we also let the work take on some important risks.

SUMMARY. On the Lansing Riverfront, we begin with problem-solving questions. At the scale of a person, those questions prompt delightful physical responses including once-impossible opportunities to interact with water. At a city scale, thoughtfully guiding new adjacencies where we work, relax, and meet creates new opportunities for economic development, prosperity, and celebration.

Questions that arise as unexpected benefits of our process continue to make us more critical and thoughtful designers. In making new landscapes, we continue to negotiate a professional context that seeks to eliminate all forms of risk. If we continue to question our approach to certainty in design and construction, we may find new ways to invest our work with meaning and richness.