“Razzle Dazzle”

Razzle Dazzle is part of a week-long installation that stems from “Parking Day,” an annual event that invites community members, students, and designers to temporarily transform a parking space. Located on West Grand Boulevard in front of the iconic Fisher Building in New Center, Razzle Dazzle seeks to achieve three objectives: to engage the user through the use of provocative form, color, and material; to create a 1:1 spatial experience; to be resourceful in an effort to reuse materials, minimize waste, and cut costs.

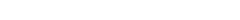

USS West Mahomet (ID-3681) in port, c. November 1918. Courtesy US Naval Historical and Heritage Command, NH 1733.

The primary purpose of camouflage is to blend a figure with its surroundings – to make invisible. The most common type of camouflage is known as high similarity or blending camouflage. But camouflage can also have the opposite effect. A.H. Thayer coined the term “razzle-dazzle” in his book “Concealing Coloration in the Animal Kingdom” (1909) to describe natural systems of camouflage that utilize disruptive and high-contrast patterns to make it indistinguishable from its environment. Take a zebra for example: it is believed that stripes make it difficult for a predator to distinguish one from another when the zebras are in a large herd. This is called disruptive camouflage.

During World War I, one of the most spectacular applications of disruptive camouflage was called Dazzle. It emerged out of a very dire problem: American and British ships were repeatedly being sunk by German U-Boats. Conventional camouflage doesn’t work on open water due to many factors, including conditions like the color of the sky, cloud cover, and wave height. As a result, British and American ships were deliberately being painted in Dazzle to disrupt the enemy, making it hard to determine the target ship’s speed and direction. However, Dazzle was never proven to actually work and it was occasionally criticized for being ineffective. But the life of Dazzle didn’t end with ships; it has influenced mainstream culture, particularly art, fashion, and graphic design.

In the context of this project, Dazzle patterning is applied to a large platform as a means to disrupt the passerby. Reclaimed 2’ x 2’ plywood cubes provide seating for an adjacent bus stop. The cubes are clad in reflective film and seemingly disappear in juxtaposition with the floor. Similar to “Cloud Gate” (nicknamed “The Bean”) in Chicago’s Millennium Park, the reflective surfaces also draw in the surrounding context, offering glimpses of buildings, sky, and street activity.