DETROIT CHILDREN’S LIBRARY : DESIGN FOR CHILDREN

QUESTIONS. How should one design for children? Should architects alter their design approach for projects with a 12 year old (and under) clientele? These simple questions marked the beginning of HAA’s design process for the renovation and expansion of the Detroit Public Library Children’s Library.

POSITION. After working through the project, HAA answered these questions with a modern design solution that empowers the intelligence of its primary users, the children. The proposed space allows for introspective investigations; each child initiates vastly different experiences in various parts of the library. Conversely, the proposed Detroit Children’s Library is also a social space, an armature for discovery that does not dictate specific responses, but provides opportunities for a wide range of collaboration and interaction. In effect, the proposed environment encourages the journey, where learning and social developments are associated with a thoughtful, compelling design.

PROJECT. The Detroit Public Library (DPL) Main Branch is located along Woodward Avenue just north of Warren and centered in the cultural core of the city. The building was designed by the renowned Beaux-Arts architect, Cass Gilbert, and completed in 1921. Two subsequent wings were added in 1963. Housed within the first floor of the DPL north wing, the existing 3500 SF Children’s Library is outdated, outgrown, and happily over-utilized. The renovated area increases to occupy approximately 15,000 SF, providing the flexible space necessary for the expanding programs of the DPL. Working with the client, two innovative concepts emerged for the proposed Detroit Children’s Library.

- The proposed Children’s Library will be analogous to a child’s journey through the learning process, and thus, through life.

- The proposed Children’s Library will be a technological center, integrating traditional program with modern technology, and thereby, redefining the modern children’s library as a locus of knowledge, cross cultural exchange, and community building.

Of course, these statements were derived from adult perspectives. So another set of questions were asked: What does it mean to take a journey as a child? What unique methods or viewpoints does a child employ on their journey? And finally circling back to the original inquiry, how should adults design for children?

RESEARCH. Embodying these two concepts in a cohesive design required an appropriate parti. Further research and analysis of traditional children’s games uncovered a common structure amongst numerous examples: Hopscotch, Choose-Your-Own-Adventure stories, Dungeons and Dragons, and the infamous Fortune teller origami game. All of these examples are reliant on a flexible framework that allows seemingly infinite possibilities within a pre-established format. For example, the Choose-Your-Own-Adventure stories have a flexible structure which results in a multitude of stories. To begin, the child reads the introductory chapter. At the completion of the first chapter, the child has a choice, and the story can continue in a multitude of ways. Once a direction is chosen, the story continues until another decision is required. After each chapter, the child has the freedom to make another choice. At the completion of the book, the child has created a unique storyline. If the child chooses to begin the book anew, an entirely new storyline can result. It is this flexible narrative, in which the child can choose their own path, that defined the Children’s Library design approach.

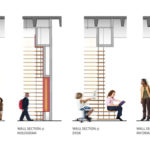

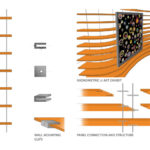

DESIGN. By extruding traditional library shelving into a single, playful element, HAA created an adaptive, physical framework that commences at the library entrance and then weaves its way towards the center of the library. The undulating wall cultivates an energetic atmosphere while simultaneously addressing a pragmatic issue by visually steering children along their desired paths. At multiple points along the journey, the children experience the freedom and responsibility of making their own choices. This spontaneity encourages creativity in both the children and the client. Technological interventions are imbedded into the wall and beckon for children’s interaction. Librarians can reprogram these information kiosks, display screens, and interactive technologies. Physically, the framework morphs between traditional shelving, wall, bench, tabletop, and artwork backdrop. Full utilization of this flexible structure encourages new experiences; children and adults can re-experience the library with each visit.

A dynamic urban library should expand and evolve with the community, operating as both a container and distributor of knowledge. For young people it acts as a point of departure where the world beyond can be revealed. This Detroit Children’s Library is designed to stimulate its users’ imaginations, encouraging them to learn through choice, form, color, and layout.

Construction for the Detroit Children’s Library is expected to begin in late 2009.